Into the midday hush of the archaeological and ethnographic museum comes an incongruously tinny beat from manager Giorgio Pala's laptop. "Island of blue; land of happiness," croons a male voice in Italian to a jaunty pop backing. "The air is mild; there's a scent of eternity." A big bear of a man with a grey beard and expressive eyebrows, Pala can barely disguise his scorn.

"What can I say? Poor guy," he mutters. "It's true that the sea is lovely; the sea is blue. OK. But I believe that the really beautiful part of Sardinia is that of the inland, far away from these places." He presses the pause button. Quiet returns to the Nuragic treasures and Roman gems.

Earlier this month, prompted by concern for the ravaged economy of Italy's second largest island, Giulio Rapetti, one of the country's best-known songwriters, unveiled a piece of music he described as a "little gift". A "joyous track" that celebrated its "colours, attractions and traditions", it was reportedly hailed by the Sardinian regional authority's spokesman for tourism as "an extraordinary advert for touristic promotion". But not everyone was equally impressed.

"Sardinia, down the centuries, has inspired a great many artists, writers and poets," wrote actress Francesca Petretto on a blog for Il Fatto Quotidiano, citing DH Lawrence and Carlo Levi. "Now, I said to myself, there's Mogol [as Rapetti is commonly known] too; who knows with what virtuosity he will choose the best words to describe the magnificence of my land?" Unfortunately for Petretto, what she ended up hearing was "a cross between an advertising jingle for Costa Cruises and Under The Sea from Disney's The Little Mermaid.

But the problem was not so much the song, motivated as it was by "praiseworthy intent". The problem, she said, was that by focusing on Sardinia's sea and beaches it had hit a nerve: the island was still failing to come up with a more sustainable kind of tourism, one that could help the whole island, the whole year round, and not just the seaside in summer.

A tourism that would, for instance, allow Pala to show off not only his museum but also the archaeological gems of his home. "Those tourists who come to see the Sardinian inland are very few," he says despondently. The few who do make it to Oschiri do so only because it's "bad weather that day at the sea", he notes. "I would like to wave a magic wand and show what Sardinia truly is."

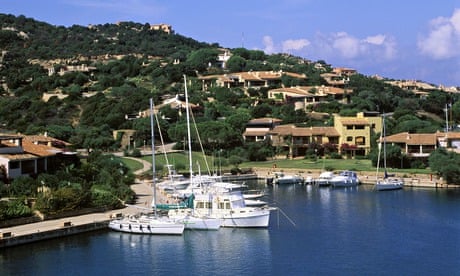

A quiet village in the heart of the northern interior, Oschiri is around 45 miles from the Costa Smeralda, the stretch of coast famed worldwide for its white sandy beaches, wild parties and Wag-like clientele. But general location is about the only thing they have in common. While a day at the VIP playground entails champagne, caviar and yachts, Oschiri's annual high point came with the Sagra della panada, a festival devoted to a delicious version of the pork pie, and replete with traditional singing and dancing. A hotel room on the Costa Smeralda can set you back thousands. In the Olbia-Tempio province around Oschiri, meanwhile, unemployment last year climbed to more than 17%, up from 13% in 2012. The gulf is stark.

Not that many Sardinians care about not being able to join in the beachside shenanigans of footballers and reality TV stars. The Costa Smeralda put their island on the international tourism map. It's just a shame, say some, that the benefit isn't spread around a bit more – especially in the largely rural and infrequently visited interior where Sardinia's culture is most fiercely protected.

"The inland is now seen as the heart of the island, because it is here that it is most characteristic and specific," says Roberto Carta, 38, an Oschiri native who works in the town council. "All the heritage – cultural, linguistic, musical, which is so rich – has been far more preserved in inland communities than it has been in the cities. There it has become something just for show … whereas here these are living customs. They are in daily use."

Sitting in a cafe opposite a church surrounded by palm trees, he breaks off to chat to a passerby in Sardinian, the language of 80% of his conversations in the village ("With all these guys here, I would never speak Italian. It'd be strange"). Carta also writes a blog, mostly in Sardinian, and it was there that he vented his irritation with Mogol's contribution. "It's a very superficial, banal little song that in my opinion does not convey the complexity of what the island of Sardinia is in its entirety," he says. But he makes it clear that the veteran lyricist cannot be blamed. What can be, however, is a form of tourism "that has no depth" and beyond which it is high time to move.

While many have thought this desirable for decades, the woeful decline of the economy in recent years has given added urgency to the appeal. According to the national statistics body Istat, the joblessness rate in Sardinia was more than 18% in the last quarter of last year, the sixth highest in Italy. More than half of households, it said, described their economic resources as either "scarce" or "absolutely insufficient".

The village of Oschiri, while it has not suffered as badly as many others during the crisis, has nonetheless been affected, mostly due to the collapse in the construction industry, says its centre-left mayor, Piero Sircana. In 2010, he said, the council advertised jobs for unemployed workers. "We needed five or six workers and 10 or 12 people applied. The next near we had about 40 applications. And last time about 100. If we were to do it now, there would be about 200, 300," he says. The other worrying trend in the village is that, for want of opportunities nearby, the young people are upping sticks. Sircana knows this well: both his children, in their 20s, have gone to Milan, and beyond, to study and work. For any place, this demographic trend is bad news. For Oschiri, where the population has been steadily decreasing since the 1950s and now stands at just 3,400, it is potentially dire.

Against this backdrop, the desire for a big, bold, new cultural tourism strategy that would help develop those parts of the island most suffering, creating jobs and boosting takings in the process, is growing. "We have to try to nurture the peculiarities of specific areas," says Sircana. "The regional authority should help us to make clear, to sustain and promote these peculiarities." Saturday's Sagra della panada was expected to draw around 10,000 people to Oschiri, a clear example, say locals, of how the vibrancy of their culture can boost the economy. "A bar will maybe take as much as it would normally do in an entire month," says Carta.

Dalila Dejua, 31, and her mother, Filippa Langiu, 62, are certainly hoping that that's not an exaggeration. Working hard in their family-run panada shop, La Tentazione (The Temptation), they are preparing "about 7-8,000" of the handmade pies for the hungry crowds. Dejua says the festival is a great opportunity not only for local businesses to make some money but also for outsiders to discover "what I think is one of the most beautiful parts of Sardinia".

"As well as the Costa Smeralda, which isn't for us," she explains, grinning, there is a huge variety of things to see. With that, Giorgio Pala would agree. The archaeological appassionato is so in love with his homeland that he almost breaks down while extolling its attributes: from the beauty of the language ("when people speak in Sard, they say things that break your heart") to the "open-air museum" of its ancient ruins.

"We're sitting on all this, but we are not managing to do the slightest thing with it. We're not managing to say: look what we have here!" he says. "If we were able to do this, I'm sure all our 1.6 million residents would all be rich. Not comfortable – rich!"

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion