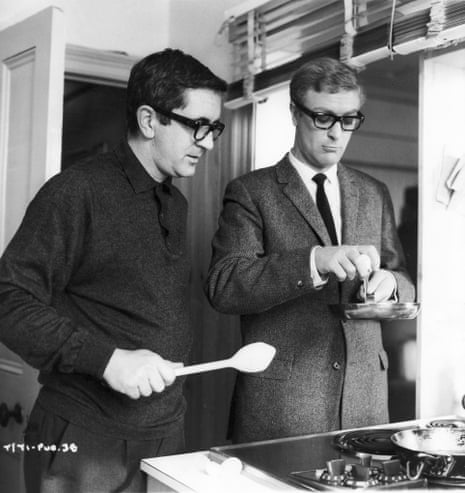

“Dump Caine’s spectacles and make the girl cook the meal. He is coming across as a homosexual.” Thus ran the furious cable from Hollywood after movie executives saw rushes of The Ipcress File, the film of Len Deighton’s blockbuster downbeat spy novel, which was being made in England.

But this was 1964. London was in full swing. Like Harry Palmer – Michael Caine’s sullen, cuisine-and-“girl”-addicted character – the British were feeling insubordinate, bolshie and confident. So, the heavy, black-rimmed glasses remained on Caine’s deadpan, alabaster face, thereby making a 60s icon; his “girl” left the kitchen work to the man; and Harry made a Spanish omelette.

In the film, as Harry nonchalantly cracks eggs into a bowl with one hand while the woman pours out two large whiskies, you can see a cluster of newspaper cuttings pinned up near the copper pans and string of garlic. They are from the Observer’s food section. Not words, but drawings – like prison-cell treasure maps dotted with arrows, numbers and scraps of staccato text veering, slightly insanely, into bold and italic. Those cuttings are some of Deighton’s famous “cookstrips”.

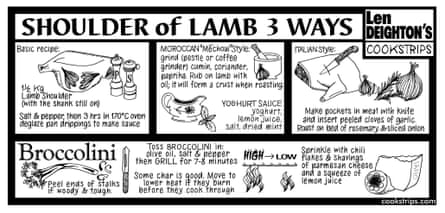

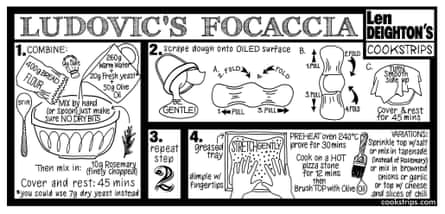

Len Deighton’s Observer cookstrips were as much a part of the 60s landscape as the pill and pot. The series – which started soon after the Beatles’ first LP, and ended the month after their last concert – made good home-cooking cool and, above all, man-friendly. Elizabeth David had already championed French and Italian food, but the cookstrips offered a new way for Britons to “do” largely Mediterranean cuisine. Black and white graphics with short explanations – an art demystified, distilled and democratised.

Deighton did his homework, befriending chefs, seeking out recipes – cakes from a Viennese woman in Hampstead, squid lore from Portuguese fishermen. The results had cred. This was the way to do chicken paprika, sole bercy or minestrone, that the way to make truite à la meunière, boeuf bourguignon or osso bucco, and, always, commands in bold or capitals – BEAT, RINSE, STRAIN, SHAPE, ADD, COVER, REMOVE, SERVE.

The strips were anthologised in two bestselling books, Action Cook Book (1965), and Où Est Le Garlic? (1966). By the summer of love, with two further mass-selling spy novels to his name, Deighton ruled over the improbable – but highly lucrative – twin empire of cuisine factuals and espionage fiction. Not bad for the Marylebone chauffeur’s son and former art student – St Martin’s, then Royal College – who, not that long before, had been earning a few quid a week in restaurant kitchens and jobbing around as a graphic artist.

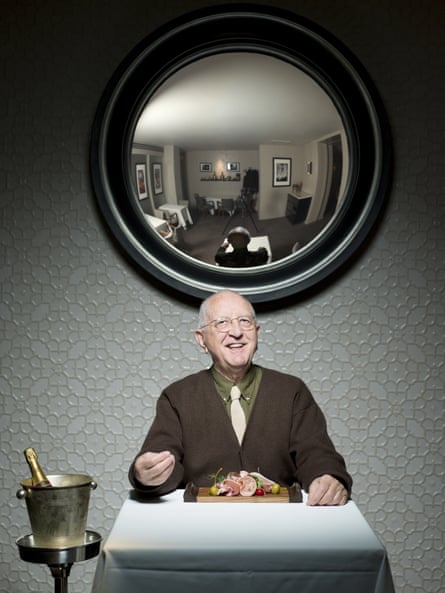

Deighton’s education in good food began early, as he explained over Dover sole at one of his favourite London restaurants, Koffmann’s in Knightsbridge. “During the war my mother was cooking in nightclubs in the West End, then we moved to Worcester Park near Epsom and she worked in the local big roadhouse type of place, doing 40 or 50 meals a day.”

Now 85 – but as trim and sharp as a 40-year-old, with the talking power of a teenager – Deighton recalls home life with absolute clarity. “She was a completely instinctive cook. She was very patient, and if I did something wrong, she wouldn’t be angry. She was able to tell you you’d got something wrong without making you feel you were a complete idiot.”

His introduction to professional cooking came in 1951. “During the Festival of Britain, I started in the kitchen at the Festival Hall restaurant, intended to be the best in London.

“I was an art student, mopping the floor. One day the fish chef’s assistant called in sick, so the chef said: ‘Put that mop down, wash your hands and help me.’ There was a mass of sole, and he showed me how to fillet one, and what else he wanted done. Next, he said: ‘I’ve told the pastry chef about you; you can help him.’”

Ten years later, Deighton started designing cookstrips – but for his own use. “I was buying expensive cookbooks. I’m very messy, and didn’t want to take them into the kitchen. So I wrote out the recipes on paper, and it was easier for me to draw three eggs than write ‘three eggs’. So I drew three eggs, then put in an arrow. For me it was a natural way to work.”

That the strips became a newspaper phenomenon is down to two friends of Deighton, art director and designer Raymond Hawkey and journalist Clive Irving.

“My wife and I went to Len’s flat a lot to eat because the food was so good,” recalls Irving. “He had these large dinner parties, mostly journalists and artists. His flat, at Elephant and Castle, was a kind of first world war museum – it had memorabilia like helmets with bullet holes, and an old machine gun – and he kept terrapins in his airing cupboard.

“One evening Ray and I were in Len’s kitchen. We noticed his stick-up drawings of cooking preparations. Ray looked at me, and I looked at Ray, and I said: ‘That could work well in a newspaper.’”

After a brief run in the Daily Express – it decided the strips were “too fancy” for its readers – Irving brought them to the Observer, where he had become design editor. Hawkey was appointed the newspaper’s chief designer. Things started happening.

“At that time the Observer’s food writer went under the name of Syllabub,” says Deighton. “He had a very loyal following, so when my cookstrips started, letters came in to the paper saying, ‘How can you inflict this on us when, before, we had Shakespeare?’ But by the time the first six had appeared, there were very supportive letters. I was paid 35 guineas each.”

The strips launched into a land where good food culture was almost unknown. “There really were signs in cafes saying, ‘Don’t expect real cream,’” recalls Deighton. “If you were lucky you got evaporated milk.” But things were changing. For the first time in decades, there was spare money to spend. A lot of it was man money. Accordingly, the cookstrip anthologies were targeted at single men, the kind who hoped that sex might follow on from a perfectly executed Coquilles St Jacques.

“At the start of the 60s it was unusual for a man to be into food – and some of the things I did hurried that process along a bit, as incomes rose,” says Deighton.

But old attitudes persisted. His publisher wanted to impregnate copies of Où Est Le Garlic? with essence of garlic, so the title “announced itself” in bookshops. “But the publisher came back to me and said: ‘I’ve got a bit of a problem…’ The warehouse workers said they wouldn’t handle the book if it smelled of garlic. So that never happened.”

Nor were Deighton’s worlds of cooking and spying far apart. He befriended Mario Cassandro and Franco Lagattolla, owners of Swinging London’s restaurant of choice, La Trattoria Terrazza, in Soho. “Sometimes I was with Mario when he was closing up, about midnight, and we would walk out on to the streets. Mario stopped outside every restaurant to look at the empty wholesale boxes left out for the dustmen. He would find out what his rivals were buying, and from which suppliers. That was a great eye-opener – a bit of espionage, that’s what it was!”

Deighton now lives in Guernsey with his wife, Ysabele. Sons Alex and Antoni have long since succumbed to the mysteries of cuisine. Antoni is an accomplished cook who, when not running his pregnancy website business babypartner.com, does high-end kitchen work such as making pastrami and smoking bacon – “I wouldn’t dare tackle this kind of thing,” admits Len. Alex is an authority on chilli, and travels the world seeking out new varieties and recipes.

“At first I didn’t have the feeling that the cookstrips were going to go on for so long,” reflects Deighton. “But, generally, you stand a better chance of succeeding in something if whatever you create, you also like to consume. I’ve never written books for people more clever than I am, or more stupid than I am. I’ve always tried to direct things at people like me. Whatever I was cooking, that’s what went into the cookstrips.”

And that expert single hand deftly cracking eggs into the bowl in The Ipcress File film – it belongs to Deighton. Harry Palmer couldn’t quite get the hang of it.

The Action Cookbook (Harper Perennial, £9.99). A new series of Len Deighton’s cookstrips will run in OFM, starting in our January issue

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion