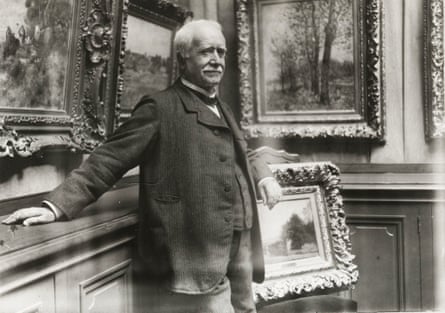

The man who invented impressionism was not a painter but a dealer – a silk-hatted monarchist with a taste for ormolu clocks who created a market for paintings that nobody liked. Paul Durand-Ruel was the saviour of Manet, Monet and Pissarro. For years he was the only dealer brave enough to promote the impressionists, helping them with their doctors’ bills, their studios and even their rent; sometimes he was their only customer.

None of this makes Durand-Ruel a hero, of course, compared to the revolutionary painters whose work he sold. So an entire show dedicated to this dealer’s activities seemed a dubious and compromising prospect. How hard could it be to sell Manet, Sisley and Pissarro, to turn Monet into a millionaire, to give Degas his one and only solo show? How challenging was it to inherit a flourishing business based on selling the ever-popular Corot? Why, the National Gallery would probably expect us to feel grateful that the reactionary Durand-Ruel managed to overlook Monet’s republicanism and Pissarro’s anarchist politics.

But Inventing Impressionism turns out to be a superb exhibition in every respect. The art is sensationally beautiful – and it is enduringly radical. That is the whole point of the show. The curators want us to see this art with new eyes – no small task given the blinding familiarity of some of these scenes: rose-scented gardens, pink-cheeked girls reading beneath sun-dappled trees, music in the Tuileries, the opera, the ballet, the bar. Is it really possible, as Durand-Ruel laments in a quotation at the entrance of this show, that the French public simply laughed?

The show opens with a stage set of the dealer’s Paris apartment in the 1870s, all chandeliers, clocks and Louis XIV chairs. Around you are the very Renoir paintings of couples dancing in the balmy dusk that hung in that salon on the Rue de Rome. Potential clients could visit one day a week to look at paintings by Renoir, Monet, Mary Cassatt or Berthe Morisot, a marketing ploy no Larry Gagosian or Jay Jopling would ever countenance today.

But Durand-Ruel knew his enemy. Look at Renoir’s bosomy nude and it seems incredible that contemporary critics could have vilified it as “a putrefying corpse”. The dealer had to make every work appear both morally and aesthetically palatable. Even though he owned a large gallery, Durand-Ruel opened his own home so that Parisians could see just how good this art looked in the setting of a bourgeois family apartment.

This set is a shrewd curatorial ploy, too, for a roomful of Renoir seems so old-world and complacent that you are scarcely ready for some of the surprises that follow – the shock of Monet’s gigantic galettes, the apple slices sharp as flick knives; Degas’s Horses Before the Stands, a quickfire experiment made using petrol paint; even Courbet’s red apples as big melons glowing dark and sweet beneath the tree, an image that plants a seed in mind for the Cézannes that come later.

It is good to see Courbet, Delacroix and a silvery Corot in this show; this was the art on which the family business was based, along with landscapes by Barbizon painters such as Charles-François Daubigny who worked directly from nature, oil-sketching outdoors before finishing their landscapes in the studio. It was Daubigny who introduced Durand-Ruel to Monet, who introduced him to Pissarro. The paintings of all three are juxtaposed in this show, so that one sees the obvious continuity through the eyes of the dealer: Monet and Pissarro were doing the same thing as Daubigny except that their canvases were fulfilled on the spot, completed in the great outdoors instead of the stuffy confines of the studio.

Durand-Ruel met Monet and Pissarro in London, where he had moved his business and stock to safety during the Franco-Prussian war. Here is Madame Monet reading a book in the grey light of a rented flat in Kensington (overtones of Muriel Spark), and Monet’s matchstick men arrayed beneath an overcast sky in Green Park (bizarre presage of Lowry). Here are Pissarro’s blue snows of Upper Norwood and his boulevards of Sydenham, breezy and fresh, dominated by local people as if the revolution might really take place in south London. These paintings feel refreshed when you see them in the context of political history and hanging alongside Manet and Degas.

You can be interested in Durand-Ruel as the first dealer to make an international business out of contemporary art – setting the market prices himself by paying over the odds for certain paintings (a beautiful little Millet – sheep, moon, shepherd, dog: what a great sonneteer and shape-maker he was) or buying back works he thought had been undervalued, such as the Manet the dealer kept for a decade until he could sell it at the high price he felt it deserved.

Indeed, Durand-Ruel emerges from this show not as the inventor of impressionism so much as the modern art industry of today. He mounts solo shows and retrospectives, publishes illustrated catalogues, develops international gallery chains; he works with sponsors, backers and exclusivity deals, issues photographs to the press, throws lavish private views, boosts auction prices and pays writers to produce essays in praise of his artists.

Manet said he would hardly have got anywhere without his dealer, and that does not seem such an excessive claim when you consider that in 1872 Durand-Ruel bought everything in Manet’s studio – 23 paintings – for 35,000 francs (40 times the average worker’s wage) when nobody else would buy a single canvas.

But you don’t have to be interested in any of this. The biographical narrative is only a structural underpinning to the show, a way of moving through time; and Durand-Ruel’s times are of course exactly those of impressionism.

Every room unleashes a surprise. From Philadelphia, the curators have borrowed Manet’s startling thriller of a sea battle between two American civil war ships off the coast of Cherbourg, all whipped blacks and fierce ultramarines (Manet once wanted to join the navy). Here is his great Boy With a Sword from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It would be hard to overstate the excitement of seeing Manet paint a cloud-racked moon or a spool of yellow peel unwinding from a lemon, to witness the brinkmanship of his knife balanced on the edge of a table.

And if it now seems impossible to imagine the nervous bewilderment of 19th-century audiences, this show helps by catching today’s viewers by surprise as well. From a private collection in Ireland, the curators have borrowed Degas’s Peasant Girls Bathing in the Sea at Dusk – a chain of dark forms viewed from behind against the dying light of the faraway sun, wildly cropped and elatingly strange, that anticipates Matisse and Gauguin.

No show that includes Degas’s orchestra pit, hugger-mugger in the glamorous darkness, or Manet’s oil sketch for A Bar at the Folies Bergère (revealing a reflection of the mysterious customer unseen in the larger masterpiece), or five of Monet’s Poplars series turning to pure abstraction in the flaring sunlight, could possibly be anything but enthralling. But this one condenses impressionism in 85 brilliantly selected works. It amounts to a history of the pictorial imagination at work in a particular time and place, and yet it takes you out of time too, into some of the most vital and exhilarating pictures ever painted.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion