On Monday 12 December 2011 a three-year ordeal, which my barrister later described as an “Orwellian nightmare”, began. I woke up to a text message from my sister: “Marcus your [sic] gonna go mad. The police are here and they’re taking all your magazines and stuff from your room.”

The British Transport Police had been on my trail for a year or so and I was well aware that my past crimes as a graffiti artist might catch up with me – associates of mine had been apprehended, as part of Operation Jurassic, an investigation into the activities of their crews GSD (Goat Squad) and YRP (Yard Raving Posse), who were prolific on trains here in the UK and overseas. My name had come up during their interviews because I’d travelled abroad with some of them to indulge in “graffiti tourism” in countries where attitudes to graffiti are more lax and permissive. What I didn’t realise was that I was to become the first person in the UK to be charged with “encouraging the commission of criminal damage” contrary to section 46 of the Serious Crime Act 2007 as part of Operation Pandora, an offshoot of Operation Jurassic focused entirely on me, Marcus Anthony Barnes, and my magazine, Keep the Faith.

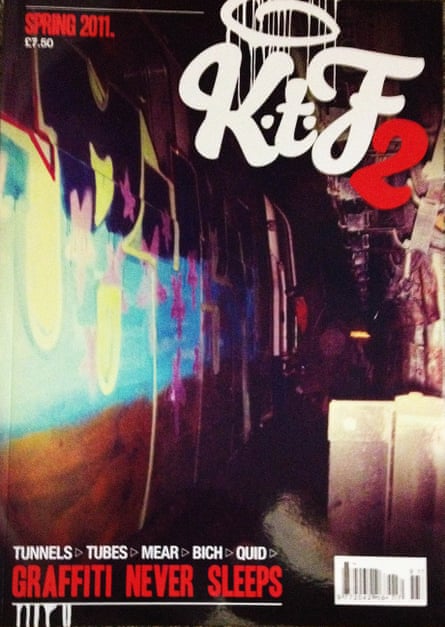

In 2010 I self-published the first issue of Keep the Faith, followed by a second in 2011. I’ve been into graffiti since 1992, when, aged 11, a schoolfriend showed me a tag (the simplest form of graffiti, a person’s name scrawled on a surface) and opened up a whole new world. In south-east London, where I grew up, I’d always seen graffiti around, but never had a clue what it meant, until that fateful day. Once I realised that the writing I saw on walls and along the railway tracks was mostly people’s pseudonyms I was hooked. In the same way one might see the names of famous actors or musicians on billboards, or brands on adverts dotted around the city’s various surfaces, these people were writing their names everywhere – it fascinated me that it was even possible for ordinary people to write their names in so many places. I wanted to do it too.

I began to tag and draw graffiti on paper. By 1995 I was travelling around the city taking photographs of graffiti, frequenting “halls of fame” – places where graffiti artists are allowed to paint legally. The name comes from the notion that having more time and space to stretch one’s legs, creatively speaking, allows for the graffiti artist to make their best work. Halls of fame are typically found in out-of-the-way locations such as basketball courts or football pitches on estates, skateparks, sometimes in disused warehouses or tunnels. In my teens I practised constantly, inspired by magazines like the now-defunct Graphotism, which featured images of graffiti on trains and in legal spaces as well as interviews with world-renowned graffiti artists – early issues featured guys like Futura2000, Phase2, the infamous DDS crew, Drax and many other highly regarded artists from London and the rest of the world.

My obsession with drawing letters and taking photographs of graffiti preceded my actual graffiti career by seven years. I was brought up with strong morals and an equally strong work ethic, thanks mainly to my mother, my nan and my uncle. The illegal side of graffiti challenged my principles and for a long time I didn’t think I was good enough to do anything in the public domain. When I did eventually pick up a spray can in January 1999, it was legally in halls of fame. Soon, though, my attitude changed and, fuelled by teen angst, I embarked on my very first mission to a train depot (known as a “yard” to graffiti artists). I lived near New Cross depot on the then East London Line. Regularly taking the train, I’d familiarised myself with several “get on” spots – places where I could access the railway tracks close to the depot, and sneak in.

That first time I set my alarm for 6am, packed my bag with paint and left the house as night was starting to become day. I climbed a 6ft fence next to a tower block that overlooked the depot, got on to the tracks and walked up to the entrance of the dormant shed, where six trains lay unmanned. I had mixed feelings – dread and exhilaration – but adrenaline kept me super-alert. I crept in under the laser trips and walked around inside for at least 15 minutes before I was sure that there were no workers or security about. Then I chose my train and began to paint.

At first I was feeling very agitated and frightened but I soon relaxed – especially when I started to layer on the black, which I used to outline my piece. In the glossy block of colour I could see my own reflection. It felt naughty, gratifying and wholly satisfying. My angst had been subdued, at least for the few hours I spent in the depot – I painted two more pieces before I left. At home I picked up more paint and went off to do a coloured piece on a wall along the railway tracks just outside New Cross station. My career in illegal graffiti had begun.

Modern-day graffiti culture began on the streets of Philadelphia and New York, but really flourished on the New York subway system during the 70s. In the early 80s a documentary, Style Wars, directed by Tony Silver, and a book Subway Art by Henry Chalfant and Martha Cooper, helped disseminate the subculture across Europe and the rest of the world. Today, train graffiti exists on a global scale, though it is still an underground culture. Many participants operate with a level of professionalism outsiders would find hard to believe. Some transport and high-level security operators describe their practices as a threat on a par with the “hostile reconnaissance” that happens before a terrorist act, but while the end result – graffiti – can be seen as a pain in the backside for the authorities, arguably a blight on communal areas, the perpetrators, consciously or unconsciously, question long-accepted norms about how our cities and spaces should be used.

For many graffiti is an obsession and nothing gets in the way; highly fortified depots around the globe are infiltrated on a regular basis. London’s yards had security fences and CCTV installed in the early 90s, when the IRA threat was at its height. Since then they have been upgraded several times to include motion sensors, laser trips, pressure pads that can detect footsteps, and tremor wires on fences that react to sudden movement, while patrolling security guards are required to check in electronically at certain points around the depot through their shift. All this at a cost, according to a 2002 London Assembly paper, of around £100m per year.

Yet the graffiti writers, determined to keep their names and the culture alive, still manage to outwit these security measures. Concrete walls are sledgehammered, fences are cut open, dug under or climbed over, cameras are obscured, security guards observed night after night until a moment of opportunity is revealed and train timetables studied and memorised, all for no financial gain.

The punishment for graffiti-related crime in the UK is high. In 2008 eight members of the DPM (DPM has several meanings including “Don’t Panic Mate” and “Da Planet’s Mine”) crew were sent to jail for between 12 and 24 months and many others have been handed lengthy custodial sentences. DPM, a collective of graffiti writers originating in south-east London who operated mainly on trains during the late 90s to mid-00s, had been put under surveillance by the British Transport Police’s graffiti unit for months and apparently allowed to paint several times before they were finally apprehended. Operation Shuttle, as this investigation was named, was one of the graffiti squad’s largest to date, costing the taxpayer around £1m and putting eight defendants on bail for two years each before trial. It involved police forces from around the world, enlisted the FBI in hacking a defendant’s email and utilised new conspiracy laws, which meant that what used to be considered relatively trivial crimes could now be dealt with with much greater severity. Funnily enough, once sentenced,some of them were asked to complete graffiti works to improve local communities as part of their punishments, according to a DPM member; one charity brought a double-decker bus into the prison that some of the crew members were in, so that they could paint it. Since Operation Shuttle, graffiti more than ever leads to prison sentences.

For around three years after that first mission on Christmas Day 1999 I was an active and prolific participant in train graffiti. I became addicted to painting them. It was all I thought about, and I’d be out at night (and sometimes during the day) infiltrating depots across London, elsewhere in the UK and even occasionally overseas. I was at university in Bristol from 2000, but still travelled back to London as often as I could to paint trains. I was arrested and cautioned in January 2000 after an associate was raided and my name, tag and number were found in his diary. I carried on but got caught again, almost red-handed, in April 2002, and I was given a fine and community service in October of that year.

That second time gave me food for thought about my choices in life and I slowed right down. I left uni and became a freelance writer. I’m now established as a music journalist but over the years I continued to paint the odd train here and there, but eventually focused more on my career and painting legally when I could.

Of course, painting graffiti in rail environments carries a risk of injury or death; walking along the lines, you could be hit by a train or slip and fall on to the third rail. Several graffiti artists have died over the past three decades. The tragic deaths of Ozone (Bradley Chapman) and Wants (Daniel Elgar), who were struck down by a westbound District Line train in 2007 , shocked our community. I knew how stupid and reckless it was when I was doing it but something inside you – call it ego, call it a buzz, or simply an obsession to make trains and their environments more interesting – overrides rational thinking and keeps you longing for that adventure, that camaraderie, that cathartic outpouring of creativity or that sense of triumph from getting one over on the heavily fortified depots.

After the deaths of Ozone and Wants, and the DPM case, a dark cloud hung over the UK’s graffiti community. I decided to lift spirits by starting a magazine. Graffiti-related media had become abundant since Style Wars and Subway Art. There are thousands of books, magazines, DVDs and websites out there covering graffiti in all its forms, from the hardcore train enthusiasts to those who craft large-scale murals and politically motivated street art. I decided to focus on what I knew best: trains. With the help of a magazine designer and graffiti artist, I launched Keep the Faith in 2010. Printing just 1,000 copies, I distributed the magazine myself, managing to get it stocked in several graffiti and hip-hop shops around the world. It did well enough for us to make a second issue, which was published in the early part of 2011 and supported by a blog, which we updated on a regular basis. The blog gained traction quickly and towards the end of 2011 we were getting close to 10,000 unique visits per month.

It wasn’t long, though, before I was raided, arrested and charged with “encouraging the commission of criminal damage” via the magazines and associated website/blog. I was on bail for more than three years until the case went to trial at Blackfriars crown court on 2 February 2015. I was in court for two and a half weeks at a cost of £28,000 per day. The prosecution’s theory was that, I/the magazine wanted to encourage graffiti writers to go out and do their worst. This, they said, was evident in the magazine’s tone of language and imagery.

It was the first time a publication had been targeted in this way; in fact, it was the first time any publisher had been prosecuted under the relatively new law. The prosecution called it a landmark case. I understood how the content could be deemed to be controversial or perhaps even offensive to someone of a very conservative or sensitive disposition, but “inciting” or “encouraging”, no. Currently, it is not against the law to publish images of graffiti on trains, nor is writing about illegal graffiti with a positive tone.

During the first week of the trial the prosecution presented their evidence against me, which centred on my bad character (previous convictions) and statements from three witnesses: DC Colin Saysell, the officer originally in charge of Operation Pandora, and DC Timothy Weekes, who had taken over as lead officer. They also called the printer of issue 2 of my magazine. From the off I could see that the jury seemed to be questioning what was going on. Notes were handed to the judge, Peter Clark QC, asking intelligent questions, such as whether outlets like Amazon are liable for the sale of magazines like mine, if they are indeed capable of encouraging people to commit criminal damage.

One of the prosecution’s key points concerned a call for photo submissions in the back of issue 2, which they claimed actively encouraged people to go out and paint, then send us their work. They also cited the tone generally, the images of graffiti writers posing in front of their trains, the magazine’s title (Keep the Faith), and used quotes from interviews I had taken part in to promote the magazine. In one of these I was asked what I thought about the state of graffiti in the UK, to which I said, “I think there’s a lot of room for improvement and we all have a hand in making those improvements, in particular the older generation, who need to make time to pass on their knowledge and skills to the younger generation. Too many old writers moan that graf is shit but they don’t make any contribution to making it any better. If there were burners (aesthetically pleasing graffiti pieces) along the tracks then younger writers might be inspired to put more effort into what they do.” That was my opinion: if graffiti looked nicer maybe people might actually like it. The prosecution asserted that this was part of my encouraging attitude, describing me as an “ageing graffiti writer passing on the mantle to the younger generation”.

The whole case was, for me, a perfect example of the archaic, hypocritical and confused way in which graffiti is viewed. While Banksy and his ilk are lauded by the establishment and media, his work covered in Perspex to protect it, and sending property values soaring, others are taken to court and even sent to prison for doing the same. Graffiti writers are hired to decorate film and TV sets – including the recent case of Homeland, where artists wrote slogans in Arabic condemning the show – or to adorn products with graffiti-style lettering to make them look “edgy” or “cool”. Police forces in the UK (Northumberland, Cheshire) and New Zealand have even used graffiti-derived styles and techniques in their own campaigns. In advertising, Louis Vuitton, Adidas, McDonald’s and Perrier are just some of the big brands that incorporate graffiti into their aesthetic. Areas like Shoreditch in London, El Born in Barcelona and Wynwood in Miami have become hubs for tourism thanks in part to the sheer volume of street art that can be found there; several graffiti walking-tour companies are capitalising on the proliferation of the art form around east London in particular. Around the country workshops now offer graffiti classes (tickets available on Groupon). There are instructional books and DVDs, videos on YouTube and a plethora of other such media, spray-paint companies that manufacture paint and markers especially for graffiti writers – even Prince Harry was pictured in the media daubing a wall with his “tag” at a hall of fame in Nottingham.

That doesn’t mean that it’s OK to paint on public property without permission, but what it shows is that graffiti is now ingrained in culture and that when it has the blessing of the media or when it’s corporatised, it’s acceptable. Would I have been investigated by Colin Saysell, former head of BTP’s graffiti unit, if I had been a publisher like Condé Nast? Or sponsored by Nike? It is not clear.

During my trial, Saysell raised the fact that he has spent more than 25 years investigating graffiti-related crime. He had put together his own “graffiti writers manifesto”, a document that uses information largely gleaned from the internet and several graffiti books, which includes a potted history of graffiti and an attempt to explain the culture. More worrying, though, was the Powerpoint presentation he gave to the court which, predictably, used images of broken windows and hoodies posing in front of graffiti brandishing baseball bats. As with any subculture, graffiti is multi-faceted, attracting participants from all walks of life with a wide variety of motives, styles and disciplines. The presentation reduced the culture by ignoring its diversity.

The second week of the trial gave me the chance to present my defence. Our “defence bundle” consisted of screen grabs from a plethora of websites including the MailOnline and its stories on Banksy’s triumphs, to press photos of Prince Harry “in action” in Nottingham and lists of the magazines, books and DVDs that could be purchased online through outlets like Amazon, an article published on vice.com that same week under the headline “A graffiti writer shows us how to paint a tube train” and even a selection of graffiti murals that had been dedicated to the victims of the Charlie Hebdo tragedy.

Our defence rested on a few key points regarding freedom of expression and speech, together with the fact that I had no intention of encouraging people to commit criminal damage with my magazine, nor did I believe the magazine was capable of this. I was called to the stand and allowed to address the courtroom.

At the end of the week our expert witness, Cedar Lewisohn, was called. He was curator of Tate Modern’s infamous Street Art exhibition, part of which involved the entire facade of the gallery being decorated by several artists, including JR from Paris; Nunca and Os Gemeos, both from São Paulo and Sixeart from Barcelona. He reiterated several of our points and gave a history of graffiti to rival DC Saysell’s presentation. After his appearance we were all sent home.

There seems to have been very little effort by the authorities to try to understand graffiti culture, to work with graffiti writers, rather than against them, and to include the public in the decisions that are made about their local environment. In the days when I was travelling around London taking pictures, the rail authorities launched the Railtrack Project, which involved several stations being repainted by graffiti artists – Vauxhall and Wallington among them. The stations looked great, both sides were happy, but, over time, the project was shelved and the station walls brownwashed once again. Communities that have allowed graffiti writers and street artists to come in and embellish shop shutters and the facades of buildings with their work often report increased respect for their local environment, a reduction in crime and a general upsurge in community relations. Graffiti art can be a positive force.

At Graffiti Sessions, a three-day conference that took place at the Southbank Centre in December 2014, Tom Fuller, service delivery manager at London Overground, revealed that his company was contractually obliged by TFL to remove graffiti within 24 hours. If not, they were charged £500 per day for any that remained on the trains. Graffiti removal cost London Overground £150 per square metre, he said. When you add up the inflated costs of damage, the expensive and lengthy investigations by the police, the price of a trial and the cost of imprisoning offenders, the total amount spent on combating graffiti beggars belief.

Ben Eine, a graffiti artist whose work was presented to President Obama by Samantha Cameron feels that the war on graffiti is ridiculous: “I think a time will come when railway companies see the value in the art they have been persecuting for years and start to embrace it as a way to add value to the passengers’ travelling experience.”

What’s become apparent to me is that a dialogue needs to be opened up between the authorities, members of the public and the graffiti writers themselves. Sending people to prison for graffiti is abhorrent. Even the judge in my case (who hates graffiti) admitted he felt conflicted when presented with people like myself who have committed “volume crime” (damage that has a high financial value) but are, essentially, decent human beings.

Frankly, graffiti writers also need to reconsider their outlook. Sure, it’s a culture born out of rebellion but many of those who practise the art form illegally place no importance on the public’s perception of their work. They contribute to the marginalisation of the culture and themselves. For some it’s a bitter pill to swallow but appealing to the public and utilising public space in a way that’s more inclusive could well aid the case for the authorities softening their view on graffiti and perhaps sparing offenders prosecution. The old adage that going down that route is “selling out” is an inflexible attitude that shows no signs of wavering among the diehards. Personally speaking, I draw satisfaction from members of the public giving positive feedback to my paintings. A piece of graffiti can be aesthetically pleasing to a wider audience without pandering to society at large or losing its power.

A small team of researchers and practitioners at Central Saint Martin’s art school in London is currently working on a project that aims to bring a more mature approach to how diverse communities can respond to, feed back on and learn from graffiti-related practices. They are investigating the notion that a community can be given responsibility for deciding the fate of graffiti in its locality, and that this process should become more democratic and could ultimately encourage a stronger connection between residents and their environment.

Marcus Willcocks, a key member of the Central Saint Martin’s team, is working with a number of authorities, artists and cultural groups from the UK and Europe, to pilot the Open Walls London project. This aims to give more public space to graffiti artists in the capital. They have also produced a range of stickers inviting people to voice their opinions and ideas on graffiti painted within such spaces. He says: “Policy and practices in the UK still commonly hold the premise that all graffiti causes harm. However, people are not asked what they do like, or what they’d prefer to see more of, so graffiti policies in our cities and transport contexts are based on complaints not ideas. What gets allowed and what does not, in our streets and public spaces, has been heavily influenced over recent decades by propagation of expensive responses to theories like ‘broken windows syndrome’ and ‘tipping points’.

Now is the time for the UK to review how much we are spending – and depending – on such measures when it is far from clear which communities they are really serving. Transport and policing policies need to be reformed to better understand and respond to communities’ and passengers’ diverse relationships with graffiti and street art.”

Professor Lorraine Gamman, also part of the Central Saint Martin’s project, told me: “At a time when local government are struggling to fund essential services, escalating the range of graffiti ‘crimes’, and demanding the criminal justice system respond, is daft. We can do better than this. We should be experimenting with new ways of making it possible to open up walls in public space so people can paint with permission – not trying to put more people in jail.”

Once the jury had been sent out, I went back to our private room next to Court 9 at Blackfriars with my barrister, girlfriend, family and a friend. Time dragged and anxiety reigned. In the end it took the jury just two hours to come to a decision. When the clerk told us they were ready, adrenaline coursed through my body. The maximum sentence for my charge was seven years. My barrister, Yogain Chandarana, told me to calm down. “Stand strong and let’s get in there.”

As the jury walk in I can’t read their faces. I put my head in my hands, unable to look, as a clerk asks them if they’ve made a decision, “Yes we have,” says the jury’s foreman. “Guilty or not guilty?” she asks. “Not guilty,” he replies and with that, a wave of emotions flows through me. As they leave the courtroom, I mouth “Thank you” at the members of jury. Some of them are smiling.

The judge tells me I can leave the dock, but reminds me that the criminal damage charges I pleaded guilty to are over the custodial threshold. A little dig to let me know it’s not over yet. It is over though – three years on bail, three years of uncertainty, over. Six weeks later I go back to court to be sentenced for nine counts of criminal damage, I received 100 hours Community Payback and an 11-month sentence suspended for two years.

Some might say, “Well, just don’t do it, you know the risks”, but it’s not as simple as that. Like it or not, graffiti will not stop, it’s part of the modern world, part of popular culture. Whether I publish a magazine about it or not, it will continue to be done. If every piece of graffiti media were eradicated from public view, if every publisher or videographer was sent to prison, even if getting caught tagging a wall meant 20 years in jail, none of this would prevent someone, somewhere, from writing their name illegally.

Equally, the law is not about to change and allow graffiti artists carte blanche to cover any and every surface at will. At the moment, we have an endless pitched battle between diehard graffiti writers and police officers who are just as obsessive, and neither side is willing to back down or communicate with the other. Each side employs ever more dastardly methods to fight the other. Cases like Operation Pandora prove how ridiculous this war has become. Let’s hope that the team at Central Saint Martin’s, and other projects around the world, can bring about some positive change and that this is the last time a case like mine is brought before the courts.

Keep the Faith magazine has been rereleased in a special bespoke package. Click here to find out more

Glossary of terms: A beginner’s guide to graffiti slang

On a mission – going out to do graffiti.

Tag – an alias or nickname. The simplest, most basic form of graffiti.

Piece – “masterpiece”. One’s tag painted in large-scale lettering, typically multicoloured.

Dub – a simpler version, usually painted in just two colours, most commonly silver and black.

Throw-up – anything from just one to a few letters very quickly executed.

Yard – train depot.

A panel is a single piece painted up to the windows on the side of a train. A top to bottom is painted all the way to the top of the side of a train. An end to end covers the entire length of a train carriage, no higher than the windows. A wholecar covers the entire carriage of a train. A married couple is two wholecars connected, and a wholetrain covers every carriage of an entire train from top to bottom and end to end.

BTees, feds – British Transport Police.

Shift – caught.

Toy – an inexperienced, incompetent artist.

Spun – raided.

Hot/bait – with a high risk of being caught.

Dogging – scrawling a tag or an insult over someone else’s piece on purpose.

Hall of fame – an area of wall space where graffiti is permitted.

Marcus Barnes

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion